Tokyo Pack 2014 – a blog

Two typhoons, a lunar eclipse and fascinating packaging

(originally published in Plastics in Packaging magazine, November 2014)

It has become something of a tradition (well, this is the second time) that I write my editor’s comment in a hotel room in my favourite city Tokyo, during a typhoon (I guess it should be expected whilst visiting Japan during the country’s typhoon season). Indeed, two typhoons and a lunar eclipse were to greet visitors to the country in the space of one week.

Japan is a fascinating country, a land with a unique approach to packaging, and an unerring knack for marrying the traditional with the modern. Packaging often transcends the simple (or sometimes not so simple) function of protecting a product to become an object that demands attention in its own right, rather apt in a culture with a strong tradition for gift-giving.

I feel almost packaged myself sat here in my complimentary hotel pyjamas and slippers watching the torrential rain pound the streets of the Shinbashi (meaning ‘new bridge’) district. It illustrates the fabulous attention to detail that you witness in so many aspects of Japanese life.

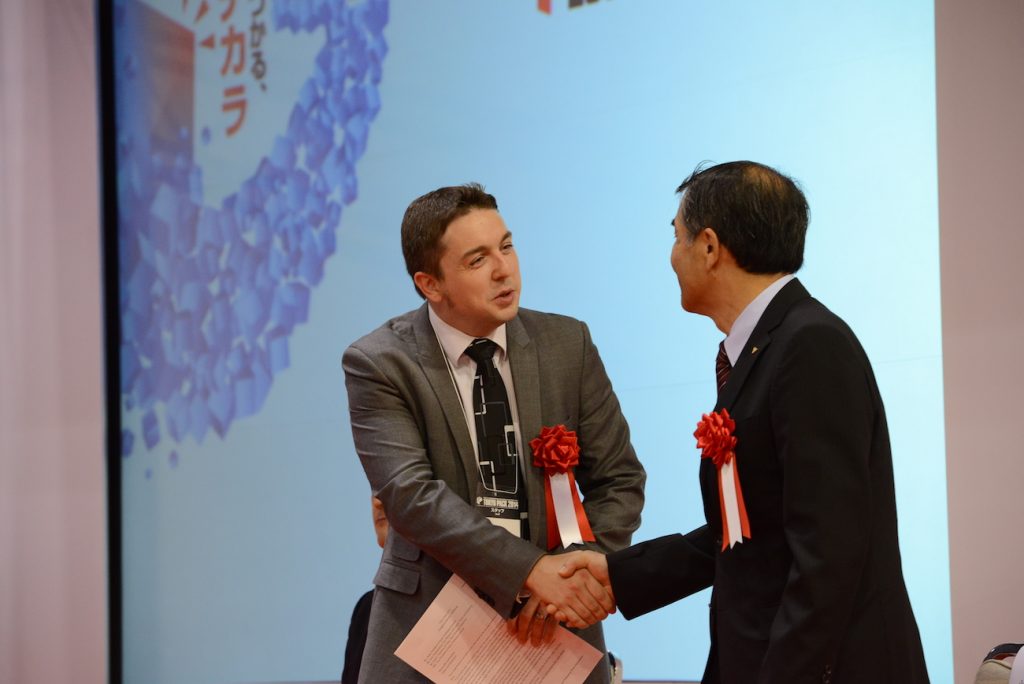

I was honoured to be asked by the Japan Packaging Institute (JPI) to deliver a speech during the opening ceremony of October’s Tokyo Pack exhibition, and to help cut the ribbon marking the opening of the 25th edition of the international show. I did this in my role not just as editor of Plastics in Packaging, but also as vice-president of the International Packaging Press Organisation (IPPO), which has had a long-standing relationship with the JPI.

The uniqueness of the packaging industry in Japan, which I discussed in my speech, was illustrated during a trip I made one afternoon to a Tokyo department store’s food hall, which proclaims itself a ‘Theatre of Food’.

I have never before seen such a diverse range of packaging in one place, from technically advanced barrier packaging formats to packs with board backing and low-quality heat-seal; the latter could be explained by the fact that some stores have staff preparing and packing fresh products such as fish in-house.

Flexible packaging is a mainstay of the Japanese food sector, with a huge variety of pouch formats, soft touch packs featuring polypropylene and polyethylene combinations, bags that combine polyethylene with metallised polyester, packs featuring a Japanese paper top-layer to provide a unique sensory experience, and polypropylene and polyamide formats to enable microwave cooking.

A conglomerate of products are packaged in rigid or flexible formats containing desiccant sachets for oxygen absorption in order to extend shelf-life. Japanese consumers are known for only trusting packs where the desiccant sachet is visible.

Shoals of fresh fish are packaged beautifully in transparent trays adorning the shelves, including sushi packed in expanded foam trays that resemble wood and transparent lids. Some fish is even presented hanging from plastics straws within the pack; no expense is spared when it comes to the aspect of presentation.

What was noticeable was the large number of fresh products featuring very short shelf-lives (Japanese consumers shop regularly, hence the abundance of small convenience stores in Tokyo, with one located every 200-metres).

Toshio Arita, owner of Packaging Strategies Japan Corporation, alluded to this during a presentation at the exhibition where he explained that 40 per cent of food is wasted in Japan (in Japan they call it ‘loss’).

The term Mottainai is used in Japan to convey a sense of regret at wastage, whether it be food or time, and it has ties with the Shinto idea that objects have souls. Arita explained that in Japan, fresh food packs often feature labels with a shelf-life so specific that it might tell the consumer to use the product by 2am the following day. He bought a Bento box (meal) that morning, which had to be eaten by 8pm on the same day. Bearing in mind that retail outlets must remove food from the shelves two hours before the ‘deadline’, it is obvious where all the wastage comes from.

In tandem with Japan’s considerable fresh food market is a view that barrier, retort and aseptic are essential technologies. It provides a great contrast. And, of course, the consumer is expected to dispose of packaging responsibly and is often required to separate the various constituents of a pack for recycling. As such, the drive for mono-material packaging is much more visible here.

Longer shelf-life is an obvious trend too in the country’s packaging, not least as a fall-out from the devastating earthquake and tsunami that befell Japan in recent years.

Just as Shinto and Zen carry a mantra for respect, simplicity and frugality, Japan’s gift-giving culture calls for perfection, while longer shelf-life calls for greater use of barrier technologies. And then you have the modern twists attached to traditional Japanese calligraphy or tea ceremonies that manifest themselves in the retail packaging, all contributing to the impressive array of products that adorn the shelves of retail outlets.

It should also be mentioned that the large number of brand companies operating in the Japanese retail space ensures that rapid innovation in terms of packaging is seen as essential, as those companies vie for market share.

The recent protests in Hong Kong, like Japanese society in general, were startlingly orderly when you consider that students would return the morning after protesting to collect for recycling the plastics bottles that littered the streets. Everything in Japan has a reason, a place, an order; it is fascinating to watch. And recycling is essential in Japan, a country with a small land mass and therefore little space for landfill.

I cannot finish without a mention of Japan’s famous Shinkansen (the high-speed bullet train), which celebrates its 50th birthday this year.